JS: Redux (React)

Theory: Reducers

We call a state everything that we store. But not all states are equally helpful. Here's the classification introduced by the Redux documentation:

- Domain data – application data that needs to be displayed, used, and modified. For example, a list of users downloaded from the server

- App state – data that determines the application's behavior. For example, the currently open URL

- UI state – data that determines how the UI looks, like displaying a list in the tile view

The store is the application's core, so we should describe the data inside it in terms of domain data and app state rather than as a tree of UI components. For example, we should not generate a state like state.leftPane.todoList.todos. It's rare for a component tree to reflect directly on a state structure, and that's okay. The view depends on the data, not the other way around.

A typical state structure looks like this:

You can find more details about working with UI states in the corresponding lesson.

We mentioned in the JS: React course that the state structure should resemble a database. Everything should be as flat and normalized as possible:

With this structure, it's easy to write a reaction to actions, update, add, and delete data. There's a little nesting, so everything is nice and clear.

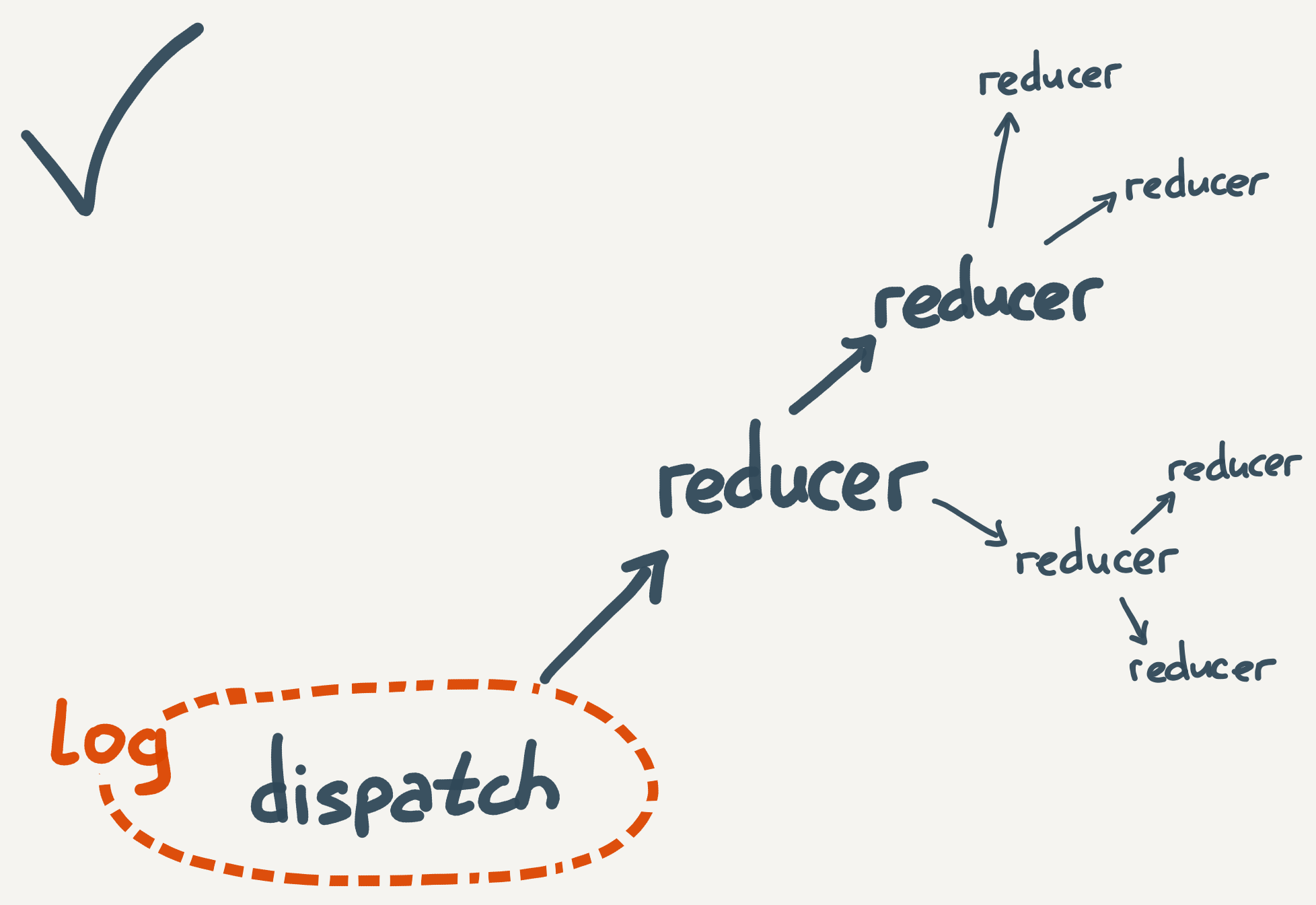

But there is one other problem which we'll always have to deal with. As the number of entities grows, the reducer gets quite hefty. It becomes a giant piece of code that does everything. To solve this problem, Redux has a built-in mechanism. It allows you to create multiple reducers and combine them.

It works like this: each top-level property gets its reducer, then we combine them into a root reducer using the combineReducers() function. Then we use it to create the store:

The state comes to each reducer, but not the store's entire state, only the part in the corresponding property. Make sure to keep this in mind.

Reducers can even be nested without any special tools. They are ordinary functions that take data as input and return new data. If you use this approach, you will find a feature that seems frightening at first glance. Since each reducer has access only to its part of the state, actions that cause changes in several places at once will be in different reducers:

In other words, we should repeat the part of the case in the necessary reducers rather than try to get the missing parts of the state.