CLI fundamentals

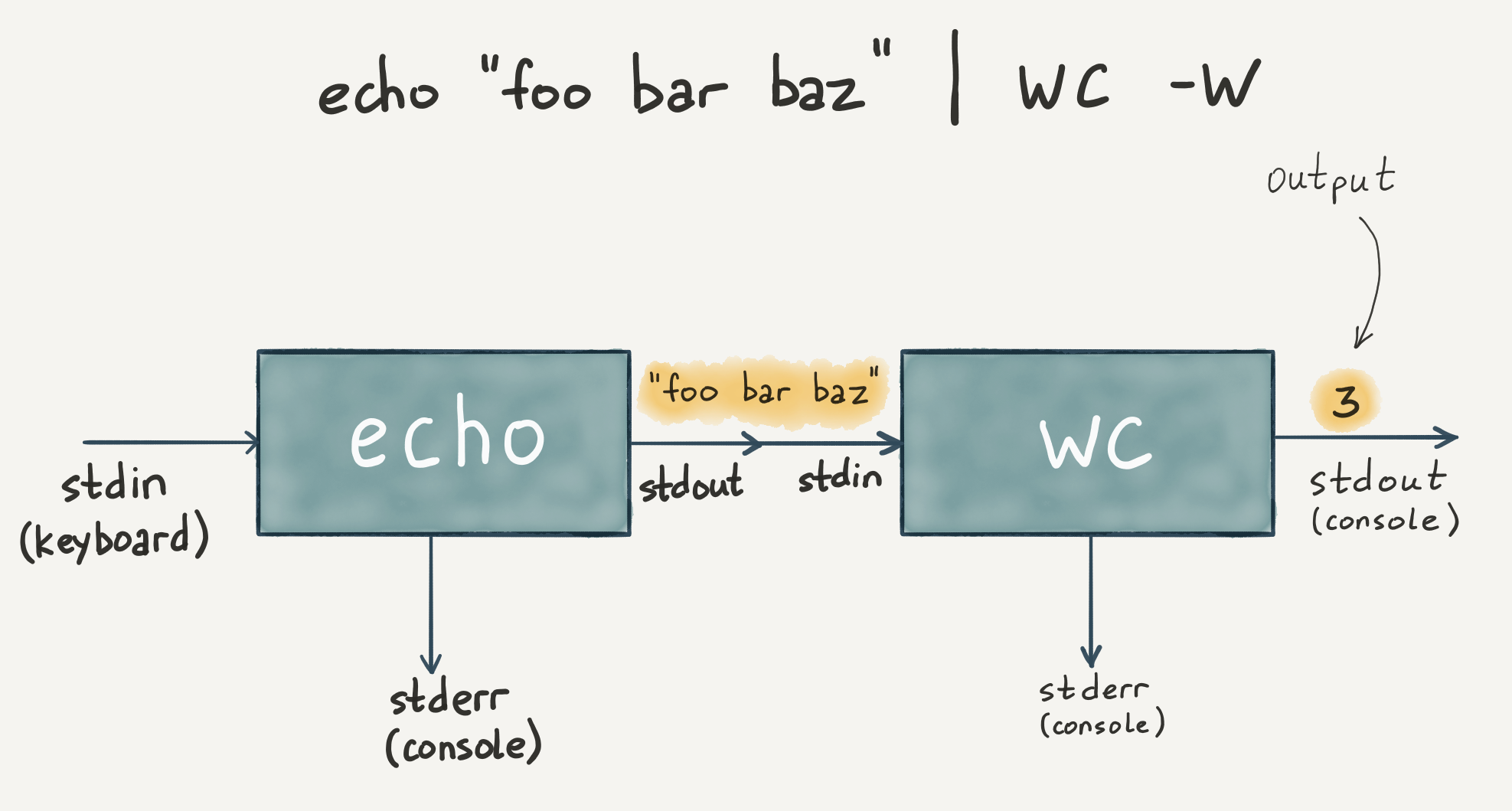

Theory: Pipeline

Since one process has an input and the other has an output, and they can be substituted, it's logical to assume that they can be connected. This approach is called pipeline. With pipelining, you can connect programs and pull data through them like a chain of functions, each acting as a converter or filter.

When we were grepping, we did it with a single word, but you may often find your self grepping with several words. It doesn't matter how they are arranged within a line, the important thing is that they meet there together. This functionality could be achieved by making the grep program itself more complicated. But pipelining allows you to achieve the same behavior without having to write a complex program.

| — this symbol is called a pipe, it tells the shell to take the STDOUT of one process, and connect it to the STDIN of the other process. Since grep takes text as input (as I said in the last lesson, all utilities that read files can take data via STDIN) and returns text, it can be combined infinitely.

The entry grep alias .bashrc | grep color can be changed using another pipe. This makes it easier to modify:

In the example above, the file is read using cat and sent to the STDIN grep.

Another example:

- Reading the source file

- Input data are grepped using the "Dog" substring

- Duplicates are removed (two identical "Dog" lines in the source file)

- The input data are sorted and displayed on the screen

Pipelining is the basis of the Unix philosophy, which is as follows:

- Write programs that do one thing and do it well

- Write programs that work together

- Write programs that support text streams, because it is a universal interface

That's why most utilities work with raw text, taking it as input and returning it to STDOUT. This approach makes it possible to get complex behavior from extremely simple building blocks. This concept is called standard interfaces and is well reflected in Lego constructors.