CLI fundamentals

Theory: File structure

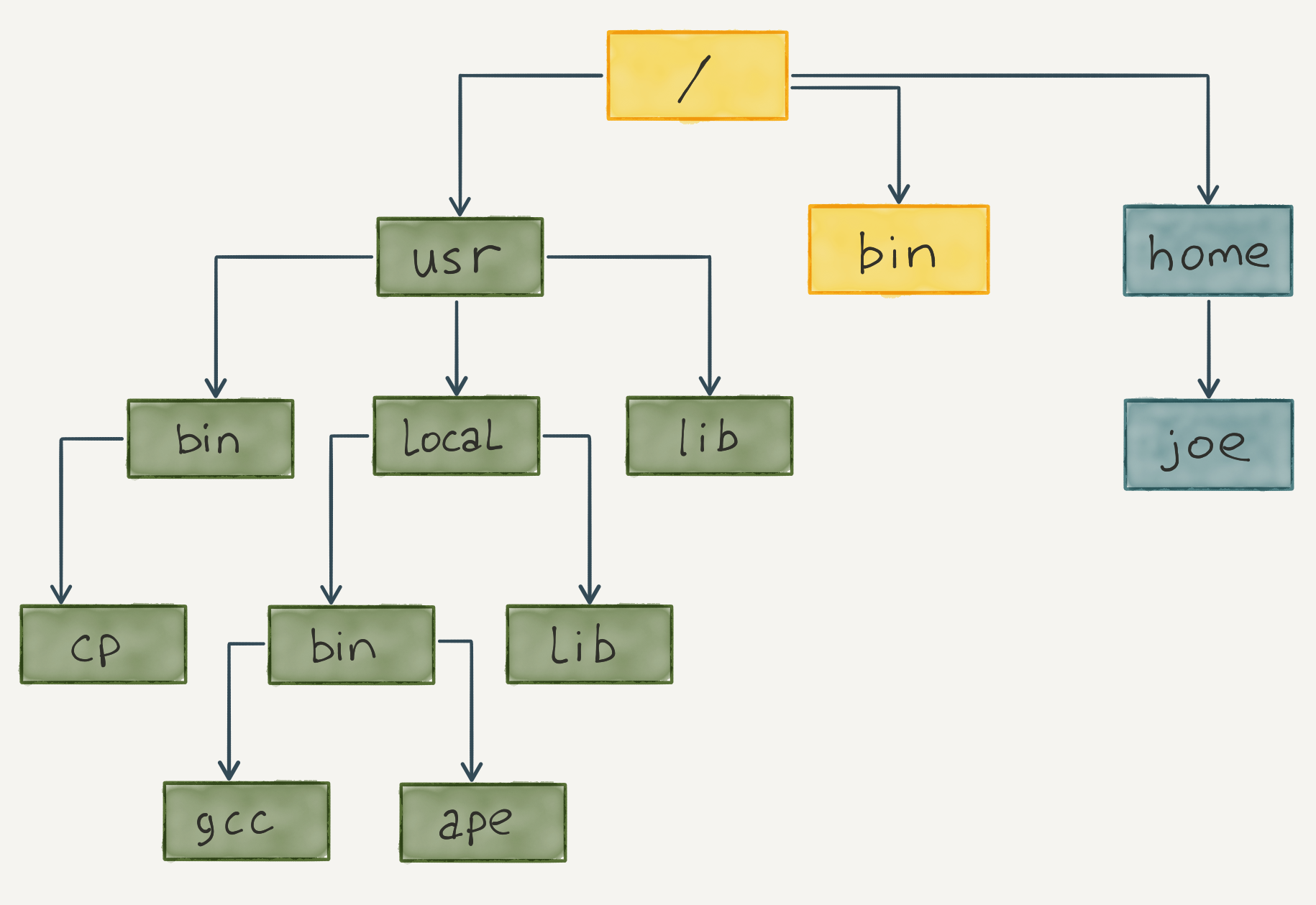

The file structure of *nix-systems is very different from that of Windows systems and deserves some attention itself. Let's start with the basics. The file structure is a tree with directories (special types of files) in the nodes and files in the leaves.

By the way, the term "folder" is not used in *nix systems, they say "directory" or "catalog", although, in fact, these terms mean the same thing.

In Windows, the file structure is represented by more than one tree, because each structure is on its own disk. On *nix-systems, the only tree with a root is in /. All devices, and physical and logical disks are inside this tree as directories and files.

Information about any file or directory is available via the stat (file system status) command:

In Windows, we're used to the fact that a file name can be typed with different cases, and it's always the same file. In other words, the names are case insensitive. On *nix systems, the case matters. The files index.html, Index.html, INDEX.HTML and index.HTML are different files. Always pay attention to the case, because it's quite easy to make a mistake.

macOS is like Windows in this situation and, as such, is also not case-sensitive

They say that in *nix, "everything is a file". On the lower level it's true (almost). A directory is a special file that contains a list of files. Any connected device becomes a file or directory if it's a drive. This concept is quite convenient for developers because printing with a printer and displaying on the screen are no different - for the code, it's just "writing to a file". At the user's level, the directory is still different from the file and has its own commands for creating, deleting, and modifying.

*nix systems have a basic set of directories which are standardized (FHS). Each one is assigned some special role. For example, the directory /etc contains configurations of programs in plain text files (there is no registry in Unix, all the configuration is in plain files), and the /home directory contains the home directories of system users (the exception is the superuser, root, their home directory is usually located at /root). Be sure to run through https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Filesystem_Hierarchy_Standard and see what's responsible for what.

Not all directories can be accessed, not all files can be read or changed, and not all programs can be run. On *nix systems, there is a well-developed system of permissions tied to users and groups. We'll discuss it separately later. For now, you just need to know that these restrictions exist. You can see them in the output of the command ls -l.

Unlike Windows, there is no concept of "file extension" on *nix systems. The dot is a full part of the name. This doesn't mean you can't understand the file type in Unix. It is possible, and also, files are almost always named the same way as in Windows, e.g., hello.mp3, but it's important to understand that this whole line is the name of the file. Names like index.html.haml are not uncommmon. *nix also has hidden files, but unlike Windows, it's not a file property but a specific filename. All files and directories beginning with a dot are considered hidden. You can output all files, including hidden ones, with the command ls -a:

Note the two special directories marked with "one dot" (.) and "two dots" (..). The single dot represents the current directory, and the two dots represent the top-level directory. This is how the cd .., command works, which moves us up a level.

Besides the usual files, there are a number of others one in *nix too:

- Hard Link — an additional name for an existing file.

- Symbolic link — similar to a shortcut in Windows. If you delete the main file, the symbolic link doesn't go anywhere.

- Socket — a special file through which different processes of the operating system communicate. Programmers constantly encounter sockets in real life.

These are the most important file types when you first start learning the file system. There are other types as well, but we won't focus on them right now.