What's a DNS server in simple words?

Have you ever wondered how the browser understands which page to open when you enter the site address in the URL bar? This is a much deeper issue than you might think. It needs to be solved in a way that isn't based on moving between sites, but on how computers are connected with each other.

In the 70s, 80s, and 90s, there was a network called ARPANET. It was an attempt by the US Department of Defense to link multiple computers together, so that they could transfer information to each other during wartime. The most important element of this approach was to be able to rapidly transmit data over long distances. Subsequently, the principles of ARPANET formed the basis of the modern Internet.

Initially, the entire network combined computers in four different US institutions:

- University of California, Los Angeles;

- Stanford Research Center;

- University of Utah;

- University of California, Santa Barbara.

The scientists at these institutions quickly came to a consensus that it was more convenient to transfer information about research to each other using the new network. In order to do this, it was enough to know the ID of the computer that the message was being transmitted. These identifiers are now called IP addresses. Every device on the Internet has this identifier, and this is what's used by devices to address each other.

At the very beginning, there were several dozen computers connected to the network, and their IDs were easy to remember. It was possible to write down these addresses in a notebook and use it in the same way as one would a phone book.

Time passed, and by the mid-80s, instead of several dozen computers, the network began to number several thousand. And each of them had a unique identifier, which became increasingly difficult to enter manually or remember. A system was needed that would humanize computer names and store all addresses in one place so that every computer on the network would have the same set of every identifier.

Contents

- hosts file — the first step to creating the DNS

- How the DNS works on the internet

- DNS resource records

- Example of real DNS records

- Conclusions

- Additional resources

hosts file — the first step to creating the DNS

To solve the problem, the developers decided to use a dictionary that linked the unique name and IP address of each computer on the network. This file was a dictionary, called hosts.txt, and it was responsible for binding IP to computer names. The file was stored on the server of the Stanford Research Institute, and network users regularly manually downloaded this file to their computers to keep the dictionary up to date, because new computers appeared on the network almost every day.

hosts.txt looked (and still looks) like this:

192.168.10.36 MIKE-STRATE-PC

Network (IP) address Computer name

Having stored this file on the computer, there is no need to remember the numbers, but the latin name "MIKE-STRATE-PC" can be used instead.

Let's see what the file looks like and try to add a new name there to connect to the computer using this name. To do this, edit the hosts file. You can find it on your computer at the following address:

- On Unix systems:

/etc/hosts - On Windows systems:

%Path to the Windows folder%/system32/drivers/etc/hosts

We specified the name "MIKE-STRATE-PC" for the computer with the IP address 192.168.10.36, which is located inside the local network. After that, you can use the ping command, which will send a special request to Mike's computer and wait for a response from him. It's like you're knocking on the door or ringing the bell to find out if anyone's home. Such a request can be sent to any computer.

With the development of the network and the constant appearance of new customers, this method became inconvenient. All users were increasingly required to download the latest version of the file from the Stanford Research Institute server, which was updated manually several times a week. To add new versions, you had to contact the institute and ask them to add new values to the file.

In 1984, Paul Mockapetris described a new system called DNS (Domain Name System), which was designed to automate the processes of collating IP addresses and computer names, as well as the processes of updating usernames, without the need to manually download a file from a third-party server.

How the DNS works on the internet

Nowadays, the internet is everywhere, we use it for both mobile and desktop devices. Video surveillance systems, speakers, and even kettles interact with each other via the Internet, and in order to communicate with them properly, we need a system through which users can connect to the desired service using just one request from the address bar. All this falls on the shoulders of the DNS system, which stores a lot more information inside itself than just the IP address and the name of the devices. DNS records are also responsible for sending emails correctly, linking different domains and domain zones to each other.

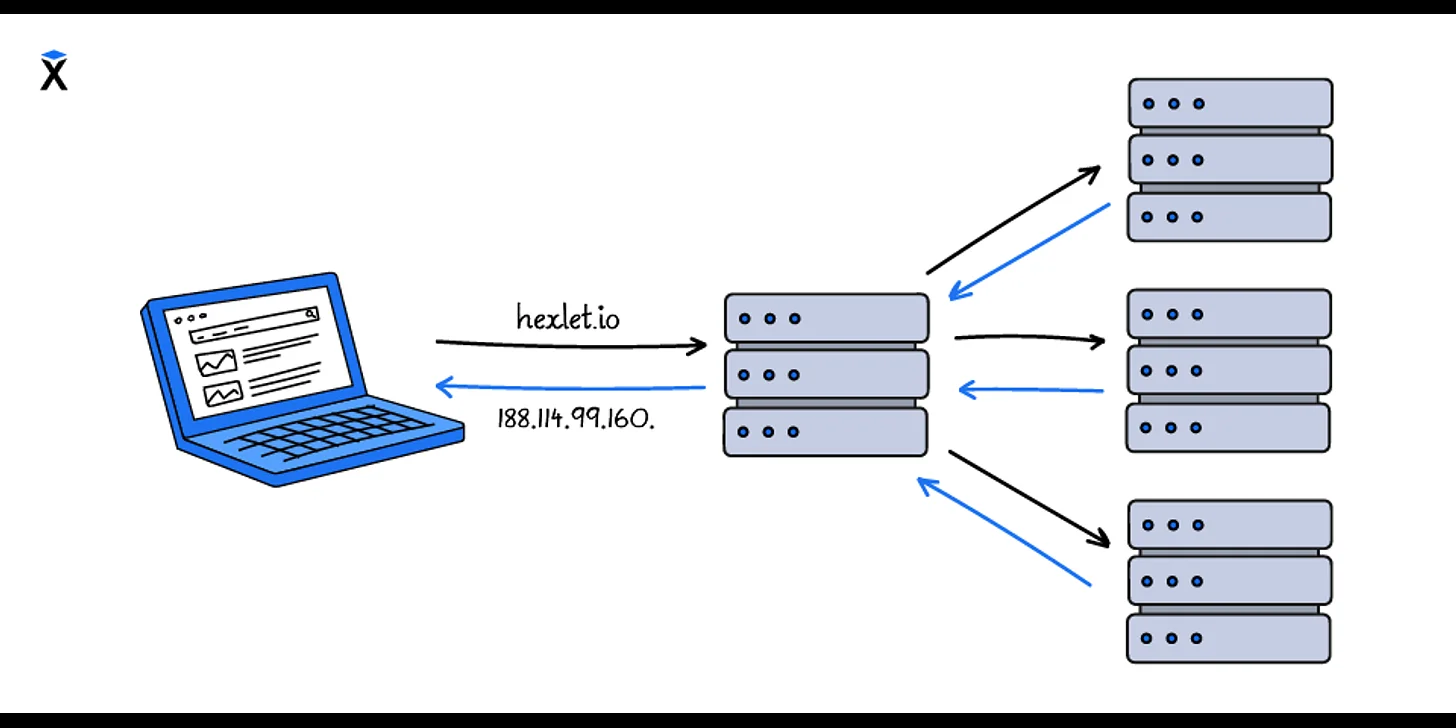

The DNS is a distributed system, meaning it has multiple nodes, each of which is responsible for its own zone. This is possible due to the fact that the DNS structure itself is hierarchical, i.e., it allocates areas of responsibility, where each parent knows about the location of its child server, and about its area of responsibility.

Let's take a closer look at how the DNS and its components work.

Terminology

The main components of the DNS are:

Domain — the symbolic name for a server on the Internet. Domain names are a hierarchical structure in which each level is separated by a dot. The main levels are:

- Root domain. It's not used in the URL, but it's always implied. All the URLs on the Internet start from this.

- Top level domains. These include .com, .net, .es, .org and so on. This domain is also called the first level domain.

- Second level domain (or main domain). This is the main name of your site.

- Subdomains (third, fourth, fifth, etc. level domains). This includes all subdomains of the main domain.

The DNS server — the system responsible for storing and maintaining up-to-date records of its child domains. Each DNS server is only responsible for its own zone, i.e. the .io DNS server knows where the hexlet domain is located, whose DNS server knows the location of its subdomains.

Root DNS-server — the system that knows the location (IP addresses) of DNS servers of top-level domains.

A resource record — is a unit of information on a DNS server. Each resource record has several fields:

- Name (the domain to which the record belongs)

- Type

- Parameters

- Value

Connection

It should be understood that the domain name is just an abstraction for people. The computer itself and applications (e.g., the browser) only access services within the Internet via IP addresses.

Let's look at the process of obtaining an IP address by domain name using the domain en.wikipedia.org.

Two variants of events are possible:

-

The computer sends a request to a DNS server it knows. Generally, it's the DNS server of the Internet service provider (ISP): What is the IP-address of the domain en.wikipedia.org?. The ISP DNS server finds information in its database stating that the domain

en.wikipedia.orgis located at the IP address 208.80.154.224 and returns the value to our computer. This process is similar to how thehosts.txtfile was used. -

The nearest known DNS server has no record of the IP address where

en.wikipedia.orgis located. In this case, a chain of processes is started which will give our computer a domain IP address:-

Since the domain is a hierarchical structure, and all DNS servers know the IP addresses of the root DNS servers, so they get a request to provide the domain IP address.

-

Root DNS servers are aware of where the DNS-servers of top-level domains are. These addresses are returned to our provider's DNS server, and after that, a request is sent to the required DNS server (in our case, to the DNS server of the .en domain) to obtain the IP address of the en.wikipedia domain.

-

In accordance with its area of responsibility, the DNS server of the top-level domain returns the IP address of the wikipedia domain's DNS server, which gets a request for the en subdomain's IP address.

-

The DNS server returns the IP addresses of en subdomain, and then our provider's DNS-server of returns this address to our computer, which is then able to access the domain en.wikipedia.org by its IP-address.

-

Recursion in DNS

You can see that both variants described above are very different: in the first instance, we just sent a request and got an answer, while in the second, we had to go from the root domain itself in the search for the record we needed. This process is recursive because the nearest DNS server continuously sends queries to other DNS servers until it gets the necessary resource records. This process can be visualized as follows:

For queries 1 and 2, the nearest server will receive information about the location of the DNS servers within the area of responsibility of the server to which the request was sent. Query 3 will retrieve the necessary resource records for the wikipedia domain and its subdomains.

For queries 1 and 2, the nearest server will receive information about the location of the DNS servers within the area of responsibility of the server to which the request was sent. Query 3 will retrieve the necessary resource records for the wikipedia domain and its subdomains.

Recursive searches are quite a long operation, are also a heavy load on the network and the DNS servers. In order to avoid recursion, each DNS server caches information about records it receives, so that they can quickly return this information to the user.

As you can see, recursive search involve finding the final answer to our query by searching through all the necessary DNS servers, starting from the root one. In contrast to this method, there is also an iterative query, which, unlike the recursive one, performs only one iteration; a query to the nearest DNS server, from which we can get both the cached response and the data from the zone it's responsible for. It is important to note that an iterative query involves only one query.

Generally, DNS servers are able to send recursive queries, because in these cases, the response can be cached, which then will reduce the load on both the server itself, and on other DNS servers. The period that the DNS server caches information for is set in the DNS resource record, which is what we'll be talking about now.

DNS resource records

The modern internet involves not just obtaining an IP address by domain name, but also forwarding e-mails, connecting additional analytics services to sites, and setting up secure HTTPS protocols. This is most often done by using DNS resource records.

Let's look at what resource records are used and what they indicate. The main DNS resource records are:

A records — are one of the most important records. This is the entry that points to the server IP address, which is tied to the domain name.

MX records — indicate the server that will be used when sending domain email.

NS records — point to the domain DNS server.

CNAME records — allow subdomains to duplicate the DNS records of their parents. This is done to redirect requests from one domain to another (most often to redirect a domain with a www subdomain to a domain without this).

TXT records — store text information about domains. They're often used to confirm ownership of a domain by adding a certain string that sends us the Internet service.

Resource records are almost always the same, but for some records, other fields may appear, for example, MX records also have a priority value. Generally, resource records have the following structure:

Record name TTL Class Type Value

Let's go into more detail:

The record name — specifies the domain the resource record belongs to.

TTL (time to live) — the time in seconds that the value of the resource record will be cached for. This is necessary to unload DNS servers. Caching means that the nearest DNS server is able to know the IP address of the requested domain.

Class — it was assumed that DNS can work not only on the Internet, so the record also indicates its class. Currently, only one value is supported - IN (Internet).

Type — indicates the type of resource record; we discussed the main ones above.

Value — means the value of the resource record itself. Depending on the type of resource record, values can be presented in different ways.

Let's see what form these records are stored in on DNS servers using the domain google.com as an example. To do this, we'll use the dig utility, which gets all available resource DNS records from the DNS server and displays them to the user.

The dig utility is a DNS client and is part of one of the most common BIND DNS servers.

Example of real DNS records

Don't be intimidated by the long output. Most likely you can understand almost everything shown here. Let's analyze the output of each section in more detail.

The output consists of several parts:

- Header

- Request section

- Response section

- Service information

Request header

; <<>> DiG 9.10.6 <<>> google.com

;; global options: +cmd

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 57684

;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 6, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1

Here you can see the flags of our request, the number of requests and responses, and other service information.

Request section

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;google.com. IN A

The request section specifies the domain being accessed, the record class, and the records we want to retrieve. ANY indicates that all available resource records need to be output, but if you want to experiment with the utility yourself, you can use a special key to output only specific records.

Response section

The response section is quite large, so for convenience let's break it down by resource record type.

;; ANSWER SECTION:

google.com. 30 IN A 74.125.205.100

The A record points to the IP address bound to our domain.

Conclusions

DNS servers now form the backbone of the entire internet and are used in almost every action a user takes, whether it's going to a website, sending an e-mail, using app on the phone, and so on. Therefore, knowledge about the principles of operation of DNS servers and basic resource records, thanks to which it is possible to navigate the Internet, are important for the developer.

Additional resources

Валерия Белякова

a year ago

0

.png)