JS: React

Theory: Performance

Premature optimization is the root of all evil.

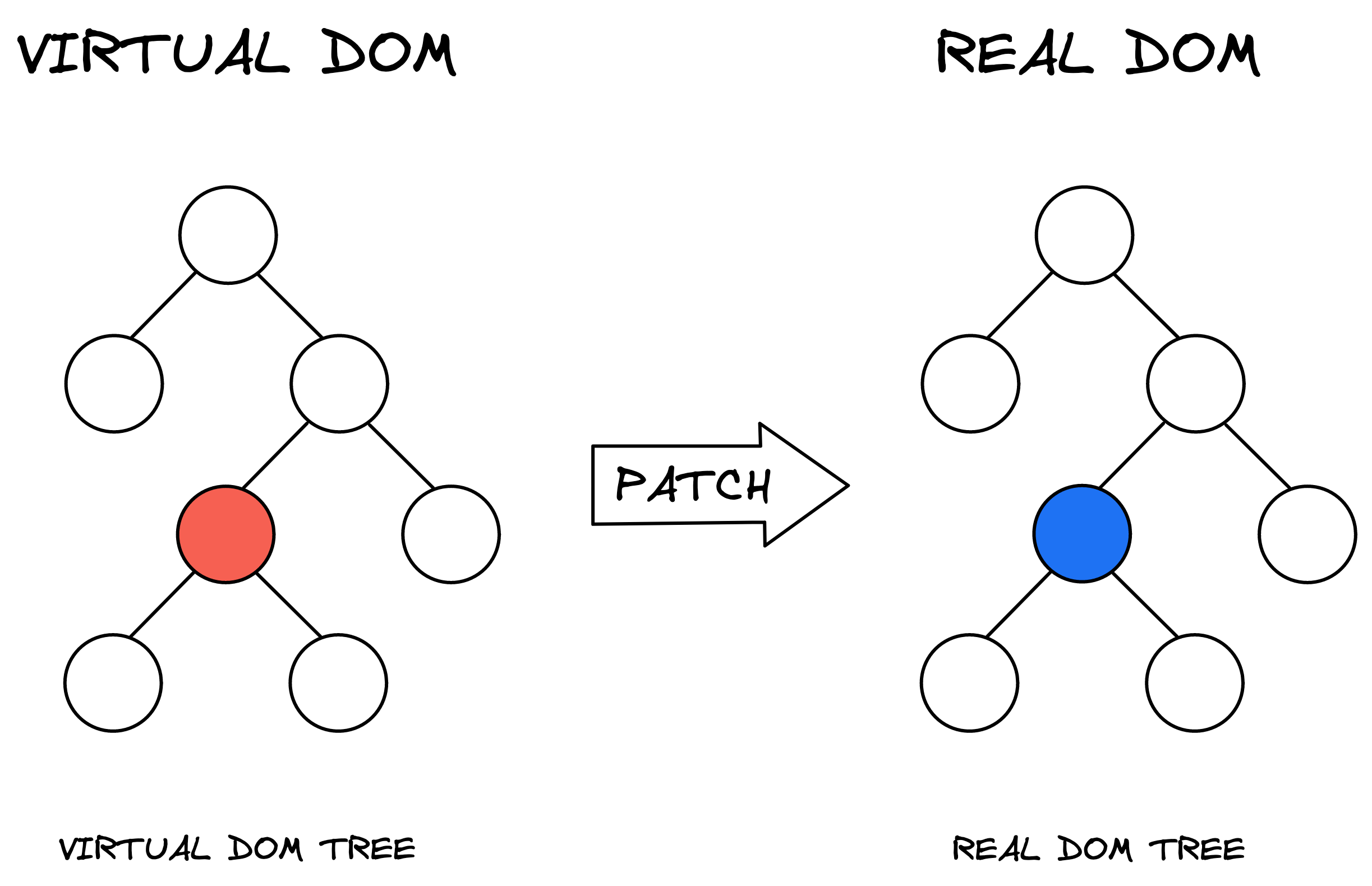

For starters, it's worth remembering that the virtual DOM is already an optimization that allows React to run out of the box fast enough that you don't have to think about performance for a long time. For many projects, this is enough for a lifetime.

In general terms, React works like this:

- Mounting causes the application to render

- The resulting DOM goes into the real DOM since there's nothing there yet. In turn, the virtual DOM remains stored within React for later updating

- The change in state causes the calculation of a new virtual DOM

- The difference between the old virtual DOM and the new one is calculated

- The difference is applied to the real DOM

Reconciliation

Every time there's a change to the state of a component, a mechanism called "reconciliation" is triggered, which calculates the difference between the past state and the new state. From an algorithmic point of view, it's essentially a search for differences in the two trees.

Generally, the algorithm that performs this calculation works with a complexity of O(n3).

If we often generate events, the virtual tree will become larger. So, the lag will increase.

To solve this problem, React insists you use a key attribute for all list items, which does not change for specific list items. This requirement allows optimization of the algorithm's performance by reducing the complexity to O(n).

The React checks the requirement for keys by itself. It will issue the warnings in the browser console if it sees you're not using them.

Rendering

In practice, rendering the entire application (virtual DOM) for any change is expensive. Imagine the application uses a text input box. During typing, any click generates a whole virtual DOM from scratch. A good example is the Q&A on Hexlet, where we encountered this problem. The forum has a large virtual tree, and its full rendering takes a certain amount of time.

The React Developer Tools extension has a checkbox showing components rendered during events.

Everything is displayed. After each event, the rendered components become surrounded by frames.

If we observe an application without optimization, we will see that any event triggers rendering. But events tend to change only a part of the DOM. For example, entering text doesn't change the DOM in most cases.

React avoids recurrent rendering of components that haven't changed. In terms of conditions – you have to keep it clean. In other words, the component must essentially be a function.

Updating components triggers the following chain of functions:

getDerivedStateFromProps()shouldComponentUpdate()render()getSnapshotBeforeUpdate()componentDidUpdate()

You can stop recurrent rendering by using shouldComponentUpdate(). If this method returns false, the component will not render.

We assume that the component behaves as a pure function, so we can check inside this method that the props and state haven't changed. It looks something like this:

The shallowEqual() function compares only the top level of objects. Otherwise, this operation would have been too heavy. By the way, here you can see why you can't change the state directly: this.state.mydata.key = 'value'. We compare objects by reference. So, changing an object will show that it is the same, even though its contents have changed.

Since most components in typical applications behave like pure functions, and we store the state in a common root component, this technique can be applied everywhere, and React actively helps with this. So far, you've only inherited classes from React.Component, but you can also inherit from React.PureComponent, in which shouldComponentUpdate has been correctly implemented for you:

See the Pen js_react_performance_pure_component by Hexlet (@hexlet) on CodePen.

If you click the button, you can see that the root component is re-rendered, but the subcomponent is not.

But it is not that simple. It is easy to break PureComponent without realizing it.

Default Props

The first issue awaits if you don't work with the default properties correctly:

It is seemingly harmless code, but calling [] each time generates a new object, assuming options is false. It is easy to check: [] === [] will be false. If not, the data have not changed, but <Cell> will be redrawn.

The takeaway is that you should use the built-in mechanism for default properties.

Callbacks

The problem in the code above is the same. We generate a new handler function (callback) for each render function call, which makes updating ineffective. You already know the solution: define handlers as class-level properties.

Immutable.js library

Another way to solve the problem of re-rendering an application is to use persistent data structures, specifically the immutable.js library. It is a separate topic beyond the scope of this course.