JS: DOM API

Theory: Navigating the DOM Tree

Studying the structure of DOM trees is the easiest way to get acquainted with them.

In short, DOM trees consist of nodes, which form a hierarchy similar to HTML. Some nodes are leaf nodes, so they don't contain other nodes inside themselves. Some nodes are internal, so they have children.

Specific nodes most often describe specific tags from HTML and contain their attributes inside themselves. Nodes have a type that defines a set of node properties and methods. In this lesson, we will get to know them below.

The root element in the DOM tree corresponds to the <html> tag.

You can access it like this:

Since <body> and <head> are always present inside the document, we can move them to the document object level for easier access:

You can go both up and down the tree:

Essentially, if you imagine a tree, you can move up to the parent, down to the child, and left and right to the siblings.

childNodes

We can use the property childNodes to get children — nodes nested in the current node on one level of nesting. Also, you can use the term descendants of the first level.

There are several interesting points to note while working with childNodes:

-

This property is read-only. Trying to write something to a specific element won't work:

To change DOM trees we have to use a specific set of methods. We will discuss them in the corresponding lesson.

-

Although

childNodesreturns a set of elements, it's still not an array. It lacks the usual methods, such asmap(),filter(), and others. However, it does haveforEach():If you want to, you can convert it into an array and then work with it in the usual way:

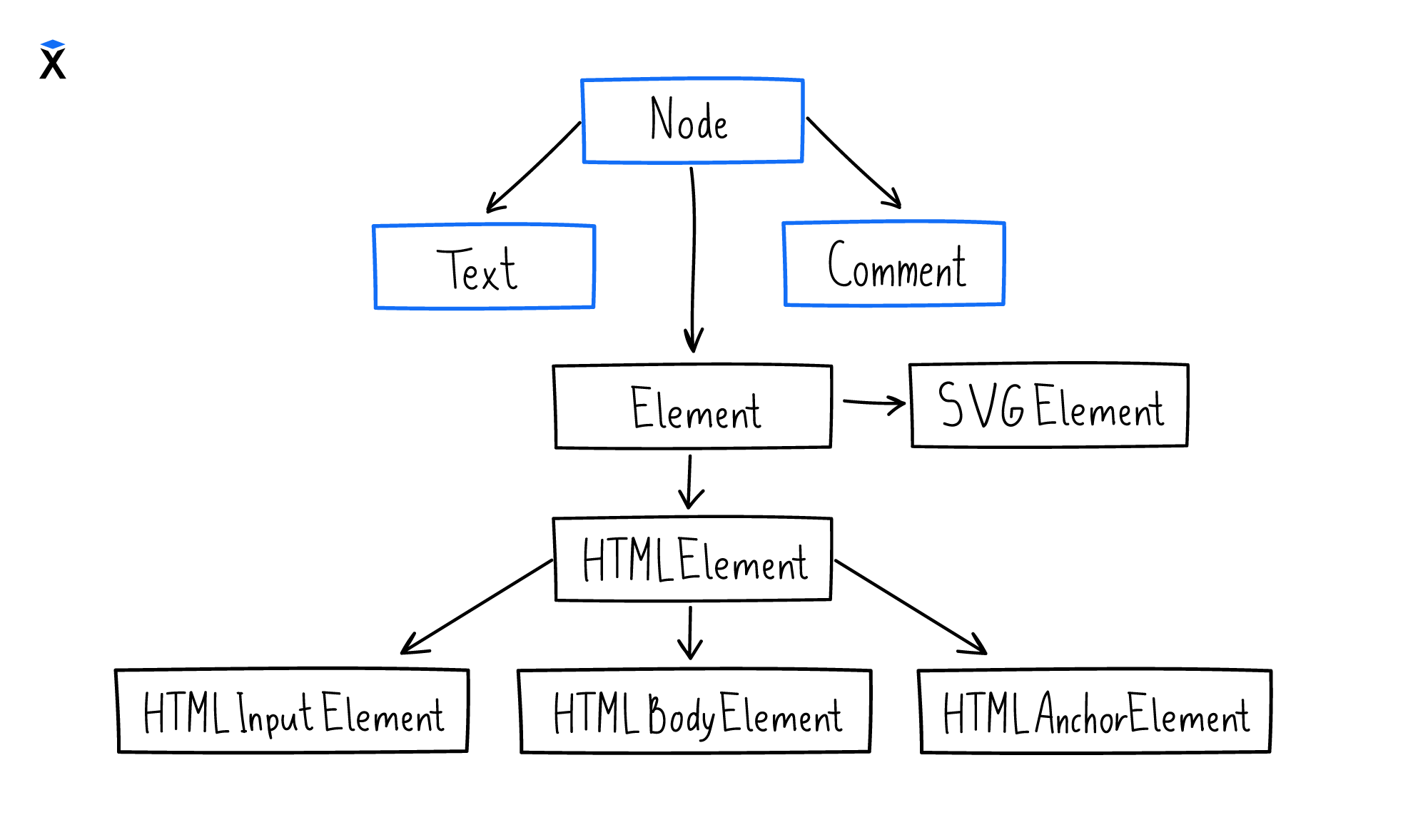

Hierarchy

The nodes in the DOM tree not only have types, but they also build a hierarchy.

In the hierarchy, subtypes inherit the properties and methods of their parent types and add their specific ones:

Nodes with the text and comment types are leaf nodes, meaning they cannot have children. But element types are what we deal with most often. The elements include all types represented by tags in HTML.

Whenever you work with a tree, you can expect to see children and descendants. Concerning the DOM tree, this means that the tag has a body, children, and descendants. How do they differ from each other?

The<div> tag with id parent-div contains three child nodes and 14 descendants. Why?

Child nodes: <h1>, text "Hello!" and <div> with thechild-div class.

Concerning the node, children are only those nodes that lie directly in it, at the first level of nesting.

Descendants are all nodes nested in it at all levels of nesting. The descendants of the <div> with id parent-div, in addition to the above three child tags, are also all nodes nested in these child tags (as well as nodes nested in these nested nodes and so on, given the recursive nature of trees).

Child nodes are also descendants. However, this isn't the same the other way round: the descendant is not necessarily a child element (in the example, the tag <span> is a descendant, but not a child to the <div> with id parent-div).

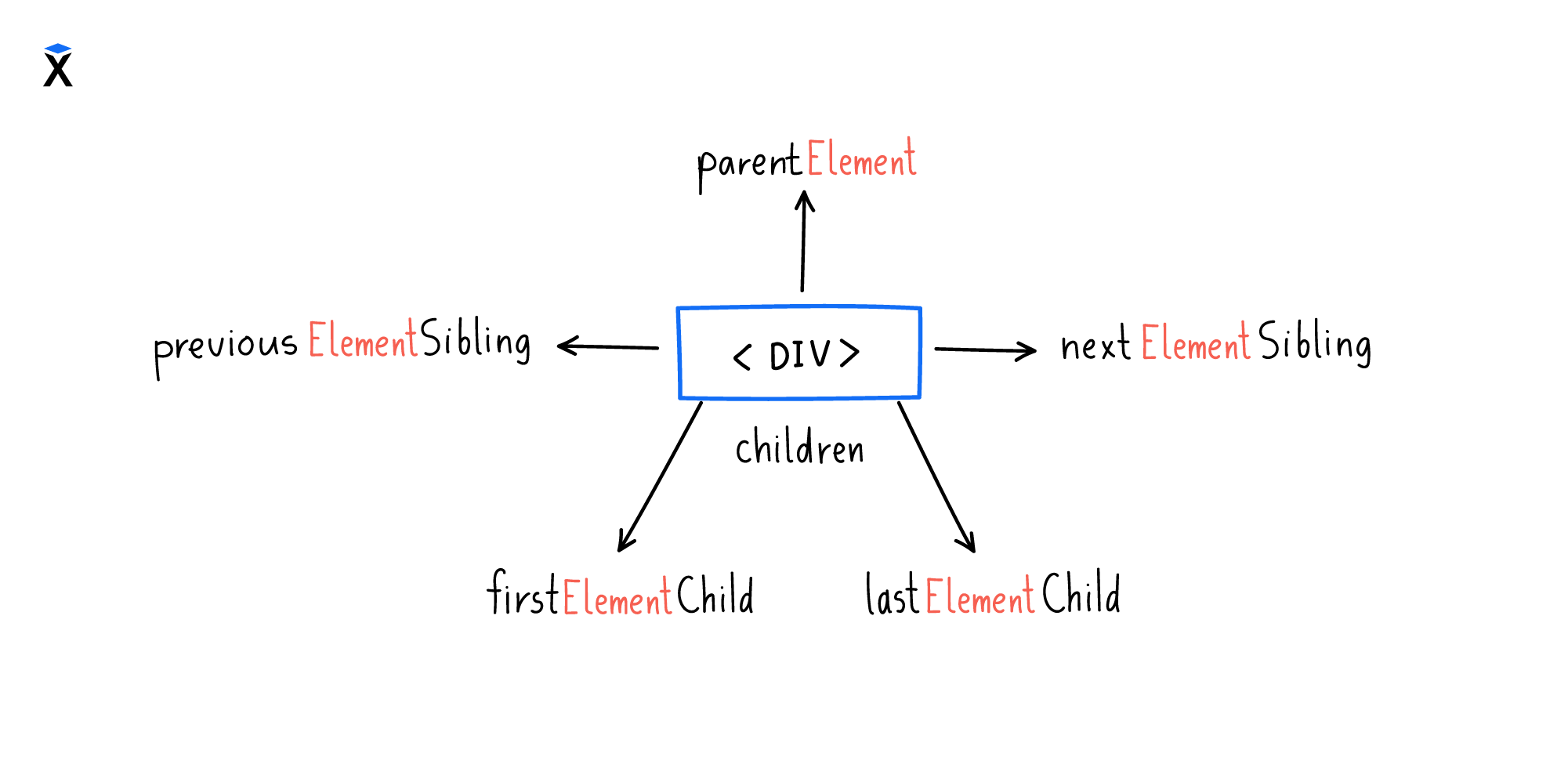

Elements

Usually, it's elements we're interested in, not just any nodes. It's elements that we want to manipulate and move through. This is so important that the DOM has an alternative way of traversing the tree, built only on elements:

All these methods return Element type objects and skip Text and Comment objects. You can see it in the example below, where the children property returns only tags. This is how children differs from childNodes, which returns all nodes, including leaf nodes:

There is another difference between children and childNodes. They return not only a different set of nodes but also different types of collections:

childNodesreturns a NodeListchildrenreturns an HTML collection

They work a little differently, but we will look at the difference later when we get acquainted with selectors.

Special navigation

Some elements, such as forms and tables, have specific properties for navigating through them:

This method of navigation does not replace the main ones. It's made solely for convenience in places where it makes sense.

Conclusion

Do we need to know all these methods by heart? Actually, no. It's important to understand the general principles of DOM tree structure. Also, you should know the hierarchy of types and the basics of traversing through elements. But that's all for now.

You can always read about specific methods and properties in the documentation. Not so many people remember them by heart, and there are no practical reasons to do so.

In addition, traversing through trees in these ways is a low–level way of working. The main way to select the elements is through selectors, which we will discuss later.