CLI fundamentals

Theory: Users and groups

The notion of users and their rights in the system is primarily related to the functioning of the operating system itself. The shell only provides utilities that allow you to analyze access rights and modify them.

Interaction with the operating system is always conducted by a specific user created in the system. The whoami command allows you to find out who you are:

Any process in the operating system starts on behalf of a user. So the process ability to affect the file system is limited to the permissions of the user on whose behalf the process is running. Note that I do not say "the user started the process", but "the process is started on behalf of the user". The point is that the user's presence is not necessary to start something. Yes, when working with the command line we run everything ourselves, but when the system boots, it runs many different processes and, as we'll see below, for many of them we create our own users with limited rights.

The ps (process status) command outputs a report about processes currently running. Information about which process is running and under which user can be obtained from the output from ps aux:

Interaction with the file system is managed by running certain utilities that modify, create, or analyze the file structure. This means that when we run touch, for example, we start a process on our own behalf, within which touch runs. It, in turn, creates a file (if there wasn't one) and makes you the owner of the new file. By the way, the modification of existing files does not affect the owner - to change it, you need to use a special utility. In the user's home directory, everything belongs to the user (although, if you try hard enough, you can make it up however you like):

The third column in this output is the owner. The only entry that stands out from the whole list is .., i.e., the parent directory. Its owner is root, which we will talk about later. If you think about it, it makes sense - after all, the /home directory is not the property of the system's users:

Each directory in the /home directory is the home directory of a particular user. Therefore, they all have different owners, usually with the same name as the corresponding directory..

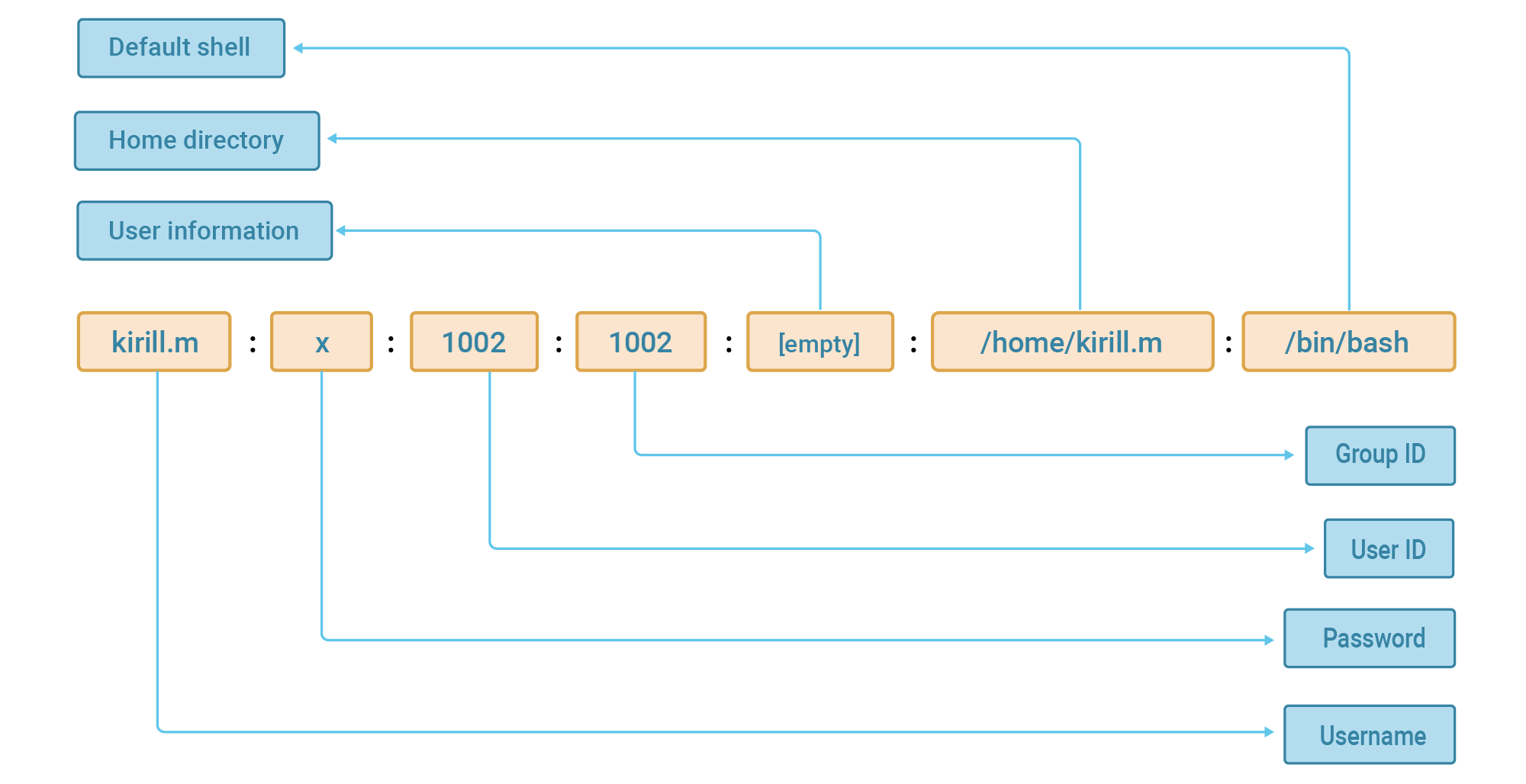

The user's name in the system must be unique, but it can be changed. If we look under the hood of this system, we see that the user's name is associated with an identifier called UID. This is the number that defines the user. If the username changes, but the ID remains the same, all accesses will remain. If the identifier changes, then the user will also, in effect, change. Naturally, the new user will lose access to everything they had. You can see your ID in different ways. The first way is with the id command:

The second way is related to viewing one important file, which is the main user storage on *nix systems. Yes, it's a plain text file, just like everything else.

In addition to the name and ID, the user's home directory is also listed here (and can be changed), as well as the default shell. The /usr/sbin/nologin entry indicates that this user cannot log in. These users are needed to run programs with limited rights, and they do not need to log in, of course.

In addition to the name, *nix system users have the concept of a group associated with them. The group, as you can guess from the name, is created for group access to a shared resource (e.g., a file). For example, we have a group of developers who regularly go to the server, and they need to be given the same rights to manage certain files. Since the file has exactly one owner, we cannot solve this issue by changing the owner, but we can do it by creating a group. It's enough to create it and bind it to the user themself. The groups associated with the current user are shown in the output of the id command:

Here, the group kirill.m is the main one, there can only be one group like this. Any files created on behalf of the current user is included in this group. In addition to the main one, the user can be a member of any number of additional groups. How this affects access rights is something we will look at in a future lesson.

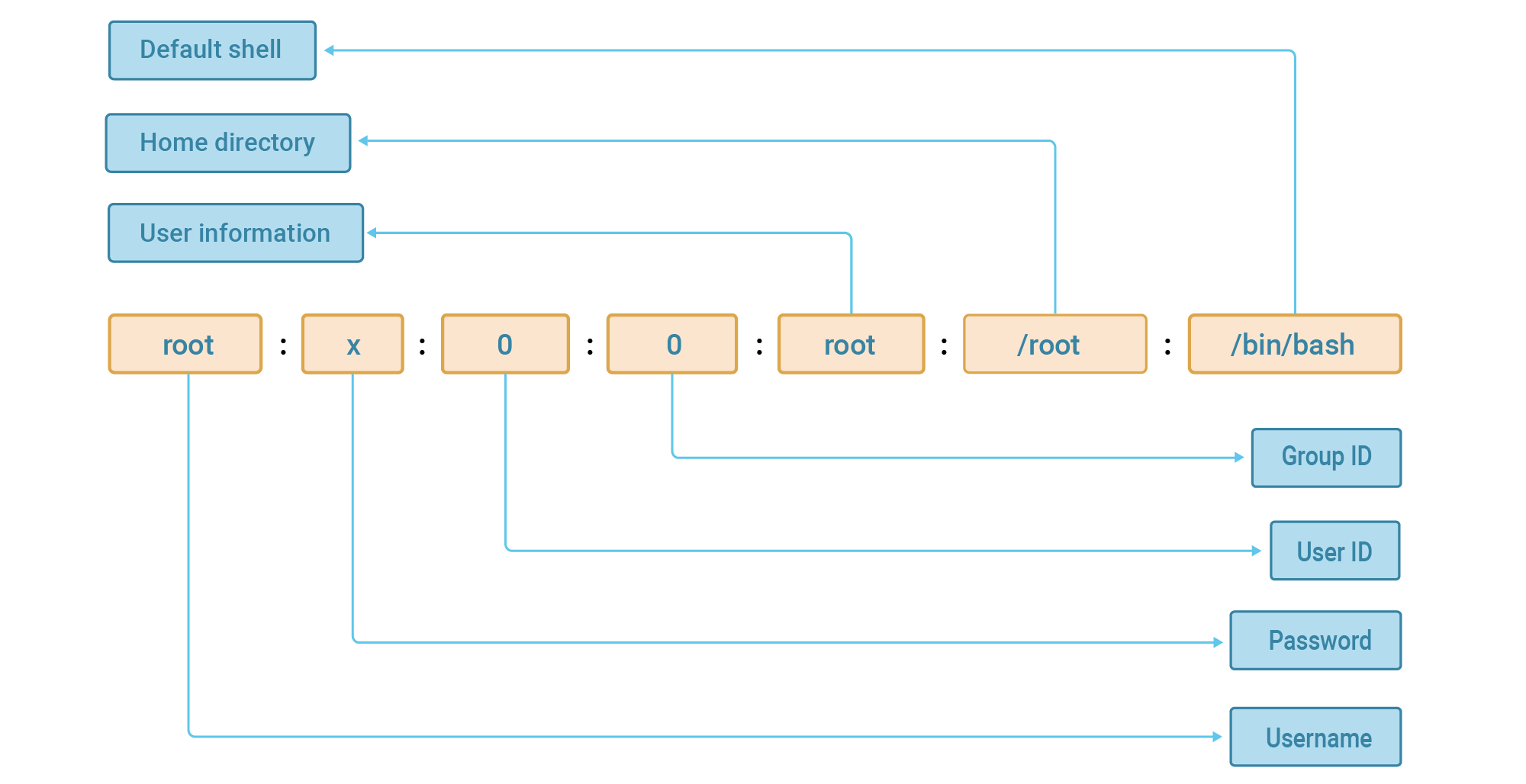

In any *nix system, there is a special root user, or, as they say, a superuser. Its main feature is having an identifier with a value of 0 (and in theory, the name can be changed). This user is especially important for the system and can perform absolutely any action in it. The root user will have an entry like this in the /etc/passwd file:

We highly discourage using this user on a regular basis. And under no circumstances should you log in as root. Root has direct access to everything and a big hole in the system's security. It's also very easy to kill the system, for example by accidentally deleting the wrong file or by corrupting some important configuration, making logging on impossible.

However, root is needed to perform some privileged actions that are not available to normal users. We'll talk about this in the next lesson.

Recommended programs

Completed

0 / 19