Python Basics

Theory: Conditional constructions

In this lesson, we will see how you can use conditional constructs to change the behavior of a program that we can make to act based on the result of a condition that it checks. It allows you to write complex programs that behave depending on the situation.

The if construct

Here we start with an example. We consider a function that works with sentences we pass and determines their type.

First, it will distinguish between statements and questions:

The if construct controls how we execute instructions. After the word if, we pass a predicate expression, followed by a colon at the end. Next, we pass a block of code. The program will execute it if the predicate is True.

If the predicate is False, the program will skip the code block and execute the function. In our case, the following line of code is return 'normal'. It will make the function return the string and terminate.

The return can be anywhere in a function, even inside a code block with a condition.

The else construct

Now we will modify the function from the previous example so that it returns the whole string Sentence is normal or Sentence is question instead of just the sentence type:

We have added a new block as well. It will execute when the if is false. You can also put other if conditions in the else block.

We can execute the if-else construct in two ways. Negation allows you to change the order of the blocks:

To make it easier, try choosing non-negative checks and adjust the contents of the blocks to match them.

The elif construct

The function get_type_of_sentence() only distinguishes between questions and statements. Let us add support for exclamations to it:

We have added an exclamation checker for exclamation sentences. Technically, this feature works, but it incorrectly interprets questions. It also has problems in terms of semantics:

- It checks for the exclamation point in any case, even if there is already a question mark

- We described the branch

elsefor the second condition but not for the first. Therefore, the question sentence becomes"normal"

To remedy the situation, let's look at another possibility that conditional constructions bring:

Now all the conditions are lined up in a single construction. The elif means:

If the previous condition is not satisfied, but the current one is satisfied

In this scenario, we get:

- If the last letter is

?, then it is a'question' - If the last letter is

!, then it is a'exclamation' - The other options are

'normal'

The program will execute only the code blocks that refer to the entire if construct.

The ternary operator

Look at the definition of this function, which returns the modulus of a given number:

But it could be written down more succinctly. It requires an expression to the right of return.

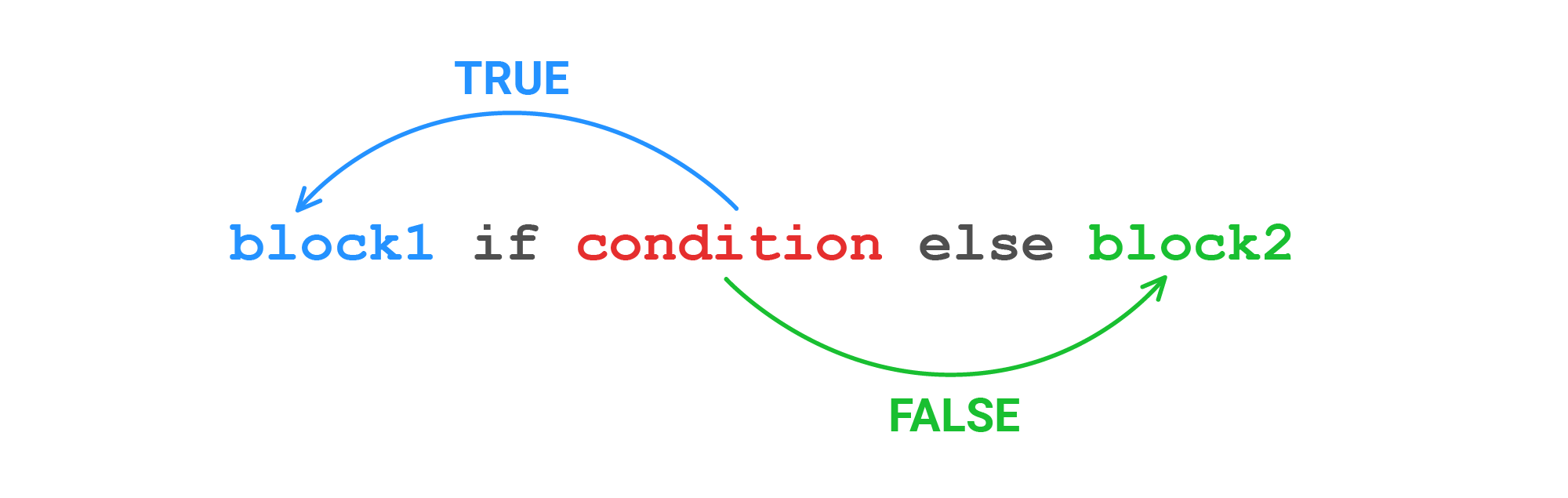

But if is an instruction, not an expression. In Python, there is a construction that works like if-else but is considered an expression. It is the ternary operator, and it's the only operator that requires three operands:

The general pattern looks like this:

Or like this:

Let us rewrite the initial version of get_type_of_sentence() similarly.

Before:

After:

A ternary operator can be nested in another ternary operator. But we should avoid it because such code is hard to read and debug.