Python Basics

Theory: Data aggregation

Another type of task that needs loops involves aggregating data. These tasks include:

- Finding the maximum or minimum value

- Finding the sum of something

- Finding the average

With these tasks, the result depends on the whole data set.

To calculate the sum, you add up all the numbers. To calculate the maximum, you compare them. Accountants and marketers will be familiar with such tasks. They work in Microsoft Excel or Google Tables.

In this lesson, we will look at how aggregation applies to numbers and strings.

Numbers

Suppose we need to find the sum of a set of numbers. Let us implement a function that adds numbers in a specified range, including bounds. A range is a series of numbers from a particular beginning to a specific end. For example, the range [1, 10] includes integers from one to ten.

Example:

Adding numbers is an iterative process, meaning we repeat it for every number. So, we need a loop to implement this code.

The number of iterations depends on the size of the range. Check out the code below:

The structure of the loop here is standard. Here we see:

- A counter we initialize with the initial value of the range

- A loop with a condition that requires to stop at the end of the range, and the counter changes at the end of the loop body

The number of iterations in such a loop is end - start + 1. It is three iterations 7 - 5 + 1 for the range [5, 7].

The main difference from the usual way of processing is the logic of calculating the result. In aggregation tasks, there is always a variable that stores the results of the loop. In the code above, it is sum.

It changes at each iteration of the loop. We add the following number in this range: sum = sum + i.

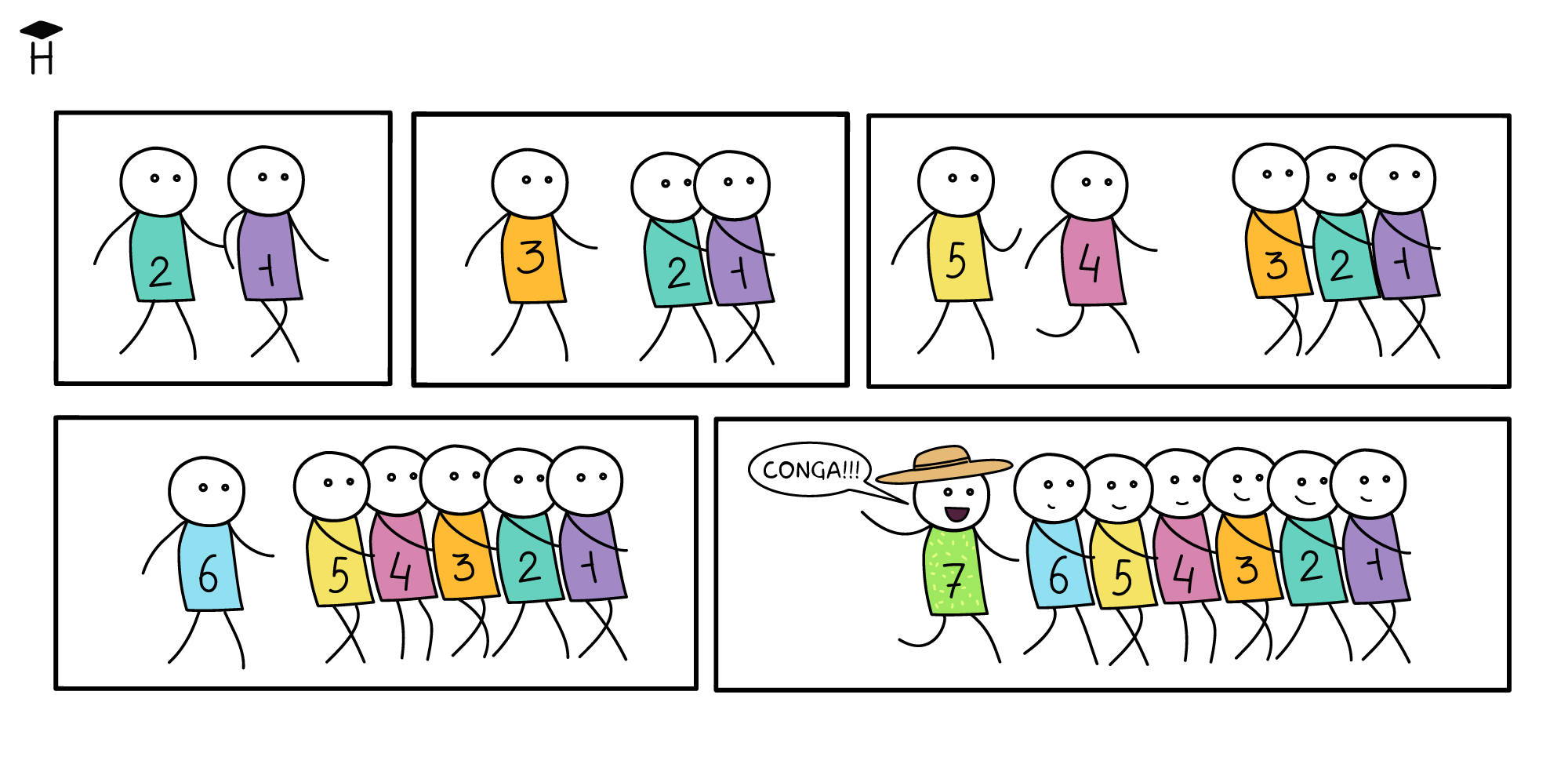

The process looks like this:

The variable sum has an initial value — the starting point of any repetitive operation. In the example above, it is 0.

In mathematics, we have the concept of a neutral element, and each operation has its neutral element.

An operation with this element does not change the value it is working on. For example, when we use addition, any number plus zero gives the number itself. It is the same for subtraction. Concatenation also has a neutral element. It is an empty string, so '' + 'one' will become 'one'.

Next, we will see how to apply aggregation to strings.

Strings

Like in the case of number aggregation, string aggregation involves not knowing what the strings contain and how big they are.

Imagine a function that knows how to multiply a string; it repeats it a specified number of times:

In the loop, we increment the string a specified number of times:

We will break down the code execution into steps: