JavaScript fundamentals

Theory: Modules

Imagine the settlers building their first small town. It only has a few buildings in the beginning: a couple of houses, a post office, and a train station. It is so small that people there can refer to any building by its name: "let's meet at the post office" or "I live in the second house" or "why are you sober, it's already 11 am... let's go... to my house.. number 1".

People were drinking a lot back then. I've heard...

Anyway, as this town grows, more buildings are built. Now the people have a choice:

- give every new building a unique number or a name

- divide the town into streets

Of course, they can go with the first option and just keep giving unique numbers and names to new buildings, so there are never two buildings number 5. This is fine, I guess, but not too great, especially for a large city. My address is "New York City, building number 654 931". Yeah, this is bad.

Most cities go with the second option: they divide the city into streets, usually straight lines, and the building identifiers — names or numbers — are set to be unique within a street. In a city, there are numerous buildings with the number 5, but they are all on different streets, so that's fine.

This is why you have folders on your computer. Without them, all of your files would be in one place, and you could never have two files with the same name. With folders, you only have to keep track of the current folder when creating a new file.

This system of dividing things into streets, blocks, or folders allows us to organize things into meaningful modules. Wall Street is a street of banking and finance, it's like a module of New York City with a specific purpose. You have a folder called "Videos" and you know it is just for videos, a specific type of files.

First programmers were the settlers in this new and weird world of computers. They faced a similar problem and had a choice to make.

They could write all the code in a single file, and this way all the things - string and number constants, variables, and functions — must have unique names. And if they want to re-use some code in another project, they have to copy it from this huge file and paste it into another file.

Or they can go with the second option: divide the code into smaller modules. Modules can be stored in separate files, and function and constant names will be unique to each file, but not the whole program. And modules can be easily re-used in different projects, without copying and pasting.

This topic is approached differently in different programming languages. JavaScript is simple: each file corresponds to a single module. You've been writing modules for all of the exercises in this course.

This is fine, but we now need to merge the code from different files in some way. If you just put code into different files, the JavaScript interpreter won't understand how to get it.

Let's look at an example: I have a file called "math.js":

This is my tiny mathematics library.

I create another file called "planets.js":

This second file won't work because surfaceArea and square don't exist here. They're in a separate file, but JavaScript doesn't know about it. We have to tell it to look inside another file. This is called "importing" — let's import everything we need:

import keyword, then the list of things we want in curly brackets then the module name. Module name is the same as the filename, but without .js. The file is in the same folder as "planets.js", so this "dot-slash" tells the interpreter to look in the current folder.

When you're importing something from China, what happens in China? Right, exporting. So, our math library should do its part — "exporting":

Just put "export" in front of anything you want to export, and this thing will be importable in another file. Here we export everything.

Back to "planets.js". Let's say we want to import more stuff. We can just add names to the list:

Or we can import everything at once:

It says "import the whole module and call it 'mathematics' in this module". Now we have access to everything exported from math module, but we have to refer to all that stuff through 'mathematics' name, like this:

mathematics dot something.

Now check this out: if we add a square function right here, it's not going to be a problem:

Here the call was made to a square function from the math module, and here the call was made to a local square function.

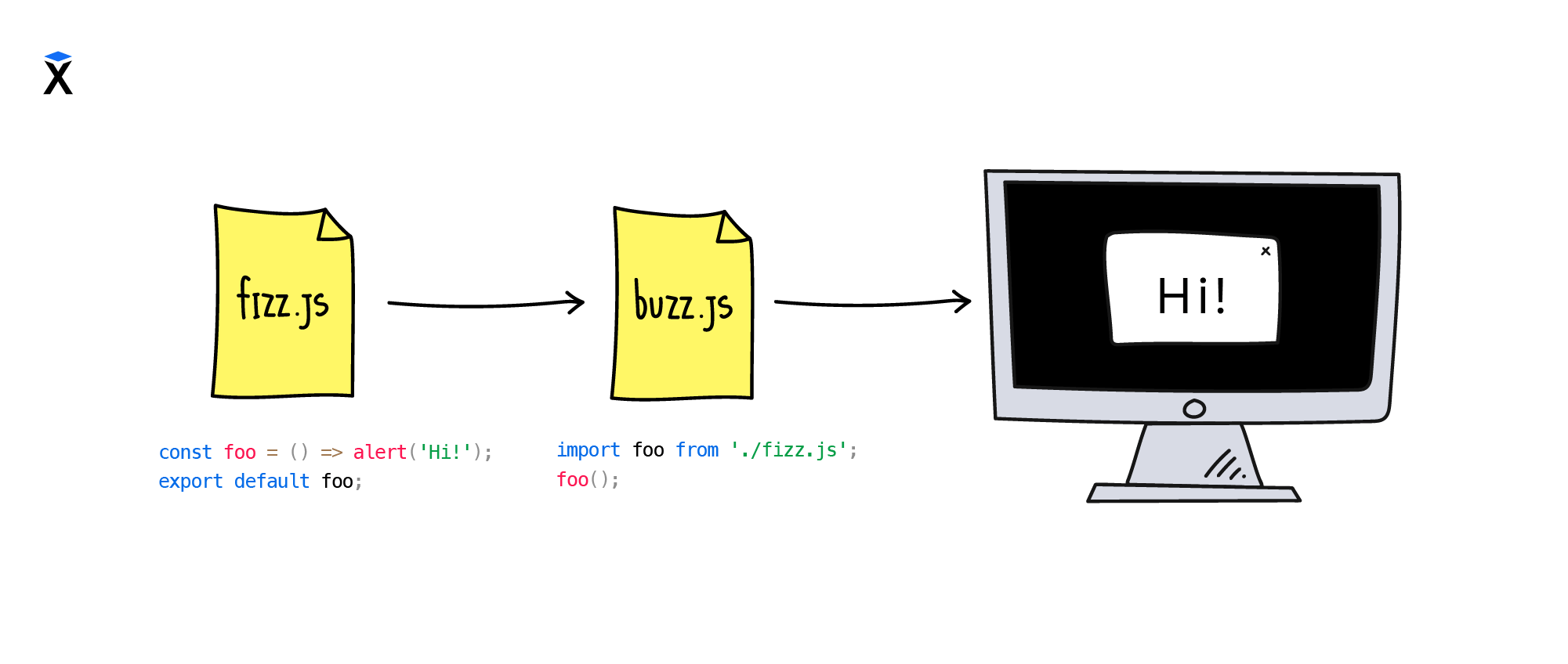

One last thing: Often you only need to export a single thing from the module. There's a special mechanism called "default export", and you can only export one thing with it. But this default exported thing is easier to import.

Just write code as usual, no explicit exports, and in the end, do "export default something". In this case, we export a function surfaceArea.

Importing defaults looks like this:

Exporting and importing mechanisms include more features, like changing the names during importing, multiple types of export from a single module and other things, but you got the most important parts.

In the current exercise you're going to create a module, export, and import a function yourself.

File extension when importing module

Specifying the file extension ensures that it will be parsed as a module by runtime environments such as Node.js and d8, and build tools such as Babel. And, while Babel allows you to omit the file extension, official Node documentation.js specifies that it must be included: :

A file extension must be provided when using the

importkeyword to resolve relative or absolute specifiers. Directory indexes (e.g. './startup/index.js') must also be fully specified.This behavior matches how

importbehaves in browser environments, assuming a typically configured server.

Summary

You can break the code up into different modules. A module in JavaScript is a single file.

The code from different modules is combined using:

- Export from a module

- Import in a module

Export and two ways of importing

Put export in front of anything you want to export. This will make it importable elsewhere:

Import specific named entities like this:

'./math' means "from the math.js file located in the same (current) folder".

Or import everything at once:

It means: "import the whole module and call it mathematics in this module". This is why imported things are refered to via mathematics like so: mathematics.surfaceArea.

Default export

You can make one item exported as default.

You can also export a function or constant without a name:

Importing a thing that has been exported as default:

When a function is exported without a name, the module determines its name at import time, hence the same export may have various names in different modules:

math.js

import1.js:

import2.js:

Supplement

Almost all the lessons of this course, as well as the rest of the courses on Hexlet, use modules. This approach brings us as close as possible to real life, when projects consist of hundreds, thousands of files and libraries that use each other.

When working with modules, it's a good idea to develop some behaviors right away that allow you to quickly understand which code is ready for execution, where it came from, and how to see it.

The basic algorithm for analyzing the file containing the code you're working on is outlined below. This algorithm isn't specific to operating in a Hexlet environment and can be used in any situation:

- Examine all of the imports listed at the beginning of the file. This will show you which modules and functions are available inside your file (excluding global functions and modules that may be used without importing, such as

Math) - Try to sort the imported functions. If the import looks like

from './...', that is, it contains./, the module is imported and its contents are stored in the current file system. This means several things. First: you can always open this file and see what is written there. Second: you won't be able to import this module in another environment (because this file isn't there) - If

from 'name'contains only the name, without./at the beginning, then the module is loaded either from the standard librarynodejs, or from installed packages. It is impossible to tell one from the other visually. Try searching for "nodejs" in Google. If the output has a link to the node docs, then this is the nodejs module; if it contains a link to the npmrepository, then this is a regular package that most likely lives on the GitHub, which can be checked with such a query: "github js"

Recommended programs

Completed

0 / 39